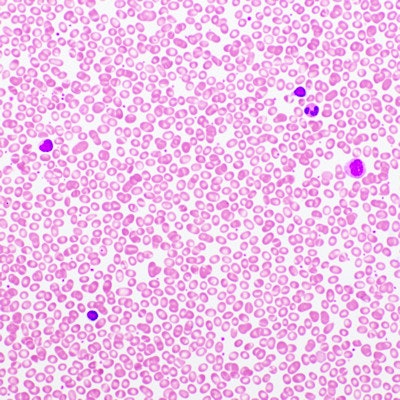

Lymphopenia, or low white blood cell count, is an independent risk factor for shorter survival, according to a large new study published in JAMA Network Open on December 2. This information is readily available through routine complete blood count (CBC) testing, so those in danger can be easily identified and targeted for interventions, study investigators noted.

The retrospective study analyzed data collected by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for a sample of 31,178 generally low-risk outpatients enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The researchers evaluated the associations between lymphopenia; other immunohematologic (IH) abnormalities, i.e., elevation of the inflammation biomarker C-reactive protein (CRP) and abnormal red blood cell distribution width (RDW); and survival, adjusting for clinical variables.

Subjects with relative lymphopenia (≤ 1,500 µL) and severe lymphopenia (≤ 1,000 µL) had significantly worse mortality based on 10-year survival rates, concluded lead author Dr. David Zidar, PhD, an interventional cardiologist and immunologist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, and colleagues. Deaths were attributed to both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular causes. Hazard ratios for the risk of reduced survival were 1.3 for relative lymphopenia and 1.8 for severe lymphopenia, the group wrote.

Furthermore, outcomes were even worse for those who also had abnormal CRP or RDW on top of lymphopenia. The presence of immunohematologic abnormalities was twice as common as type 2 diabetes and was associated with a strikingly higher risk of dying earlier.

"Individuals aged 70 to 79 years with low IH risk had a better 10-year survival (74.1%) than those who were a decade younger with a high-risk IH profile (68.9%)," the authors wrote.

Many people at risk

Zidar and colleagues view their study as the first description of the complex associations among immunohematologic abnormalities and survival in the general population.

"We found that the risks associated with these abnormal IH parameters are not only independent of, but possibly synergistic with, each other," the authors wrote. "This observation could be consistent with a conceptual model in which an adverse inflammatory status, when severe and/or protracted, leads to end-organ effects, such as anisocytosis and/or lymphopenia, before disease incidence."

Research suggests that about one-fifth of adults in the U.S. have a high-risk immunohematologic profile.

"Because the IH profiles defined herein emerge from routine testing, ensuring that these high-and extreme-risk individuals receive appropriate evidence-based disease preventive services (cancer screening, vaccination, lifestyle changes, and cardiovascular risk factor modification) may be a pragmatic, simple way to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of population health efforts," the authors wrote.

Study limitations included a lack of information about the specific cause of death; more research is needed into the diseases associated with the abnormal IH markers. The researchers also used an observational design, which makes it difficult to tease apart cause and association, they acknowledged. Implications for hospitalized patients are also unclear based on the study data.