Screening for cervical cancer through a Pap smear was introduced slowly in the 20th century, becoming a standard of care in the 1960s and 1970s. Much of this progress is due to the efforts of Dr. Elizabeth Stern, a pioneer in the field of cytopathology. Stern was instrumental in identifying dysplasia, or abnormal cells on the cervix, potentially allowing for early detection of cervical cancer.

Early years

Stern was born on September 19, 1915, in Cobalt, Ontario, the fifth of eight children to immigrants from Poland. She pursued medical studies at the University of Toronto and graduated from medical school at age 23 on June 8, 1939. A year after graduating from the University of Toronto, Stern married Solomon Shankman, a doctoral student in chemistry.

Together, they left Canada, immigrating to the U.S. in 1940 and settling in Los Angeles. There, Stern completed her residency training in pathology at Cedars of Lebanon and Good Samaritan hospitals.

For a decade, Stern served as director of laboratories and research at a cancer screening center, until she was hired in 1961 by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine as chief of the cytology laboratory. This marked the start of her research in the department of pathology, according to an article in Scientific American.

The cytopathology landscape in the 1950s was such that the Pap smear, named after Dr. George Papanicolaou who developed it in 1928, began to be used as a screening test for uterine and cervical cancer. Papanicolaou had been studying variations in vaginal smears in women and began conducting the technique, which came to be known as the Pap test. Seeing the value of the Pap test as a prevention tool against cervical cancer, cancer societies in the U.S. and Canada began to endorse and promote the Pap test.

There remained, however, room for improvement in the detection of cervical cancer as physicians were uncertain as to how to diagnose the initial stages of cervical cancer using cytopathology reports. Stern sought to define the stages of cervical cancer through her research and characterize dysplasia and shed light on its role as a portent of cervical cancer.

Stern's research location soon shifted to the UCLA School of Public Health, where she had been named professor of epidemiology in the 1960s. Stern had already begun to dedicate her energies to advancing cytopathology and was working on her hypothesis that abnormalities of cervical cells could be an early warning of cervical cancer, according to the Scientific American story.

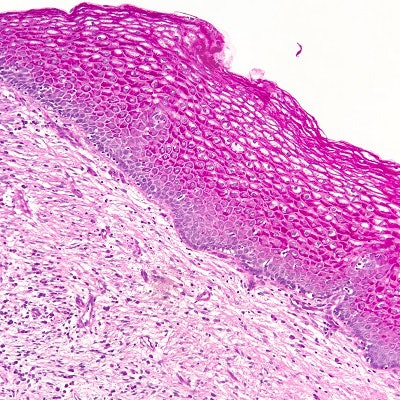

With her team, Stern conducted a study in which Pap test samples were collected from more than 10,000 women in Los Angeles County. The results of the study were published in 1963 in Acta Cytologica and demonstrated that most women who had cervical cancer at the end of two years of follow-up had cervical dysplasia detected at study entry.1 The data suggested dysplastic cells on the cervix were possibly precursor lesions of cervical cancer.

Stern's work went further later on, as she and fellow researchers developed a 100-point scale on a gradient, outlining histological analysis of cervical cancer, detailing the beginning stages of cervical cancer, and specifying the abnormal cellular morphology associated with cervical cancer.2

Oral contraceptives and cervical cancer

Another key accomplishment of Stern's was research linking the use of the oral contraceptive pill, mestranol/noretynodrel (Enovid), to the development of cervical cancer. The introduction of Enovid was a game-changing innovation in the 1960s, associated with the sexual revolution and the women's liberation movement.

The efficacy of the oral contraceptive had been established, but safety concerns in that era were not foremost in the minds of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Stern took a critical view of the oral contraceptive, and she postulated that the high dose of estrogen in the oral contraceptive was putting women at risk of cervical cancer.

In collecting data on those 10,000 women in Los Angeles County, Stern also gathered information about their contraceptive use. Looking over a seven-year period, Stern found that women using Enovid, which carried a level of estrogen 10-fold greater than what is found in today's oral contraceptive, faced a six-fold elevated risk in the development of cervical cancer. The results of this research were published in Science in 1977.3

The findings in the paper published in Science were practice-changing, as they led to combined oral contraceptives being removed from the market because of concerns around their safety for long-term use.

Stern's research also revealed that women who were mainly Black and Hispanic were experiencing the highest rates of cervical cancer in Los Angeles. Stern's observation spurred her social activism as she launched a pilot study, opening clinics in marginalized communities with a goal of providing medical care to these women.

In this community outreach experiment, women were provided with transportation and baby sitting to remove barriers to accessing medical care. Only female healthcare professionals performed the Pap tests at the clinics, which Stern and her co-investigators noted led to a greater uptake of women frequenting the clinics to undergo screening. She described the study in a 1979 paper in Medical Care.4

Stern's vision of accessible community healthcare lives on, as there are numerous points of care for women in Los Angeles County with women's health services being available free or at a low cost.

Final work

One of Stern's last projects was a technological innovation where she worked with a private laboratory and the head cytopathologist at UCLA to use computer imaging technology in Pap screening. They developed a liquid-based sampling system where the cervical scrape specimen was placed in a solution of Mucosol and an automated digital image analysis system was used to analyze cervical epithelial cells.

Stern died of stomach cancer on August 18, 1980, about a month shy of her 65th birthday. In a memorial for her issued from colleagues at UCLA, they noted that Stern persisted in the face of adversity, continuing to teach and do research after being diagnosed with stomach cancer and receiving chemotherapy as treatment.

According to her colleagues, Stern was aware that her life may be cut short because of her illness, and she took steps so that others could continue her research, such as completing a library of cytologic slides that displayed 250 discrete degrees of progression of cells from normal to cervical cancer.

Marilyn Winkleby, MPH, PhD, professor of medicine, emerita at the Stanford Prevention Research Center, who began her career under Stern's mentorship, as told to Scientific American recalled: "I remember her being alone in her office working on her science. That's the picture I have of her. Sitting right outside her busy science lab. But the door was always open; the door was never closed."

The influence that Stern has had on today's cytopathology practice cannot be overstated. Dr. Brooke Howitt, a gynecologic and sarcoma pathologist and associate professor of pathology at Stanford University School of Medicine, described to LabPulse.com the significance of Stern's work to the field of pathology.

Howitt notes that it was a novel concept to identify precursor lesions associated with increased risk for developing cervical cancer. Stern recognized that these lesions could be identified, and she developed a scoring system with increasing risk of carcinoma and worked on technology similar to today's liquid-based Pap test.

"Elizabeth Stern was among the first women to study cytopathology, and she provided insight on a cell's progression from a healthy state to a cancerous state. Dr. Stern was truly a pioneer in describing cervical dysplasia on Pap smears," Howitt wrote. "Dr. Stern conducted a number of seminal studies showing that dysplasia increased the risk for cervical cancer. Her groundbreaking research has contributed to the foundation of today's modern understanding of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cervical cancer."

- Stern E, Neely PM. Carcinoma and dysplasia of the cervix: A comparison of rates for new and returning populations. Acta Cytol. 1963 Nov-Dec;7:357-61. PMID: 14074943.

- Stern E, Forsythe AB, Youkeles L, Dixon WJ. A cytological scale for cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1974 Sep;34(9):2358-61. PMID: 4843536.

- Stern E, Forsythe AB, Youkeles L, Coffelt CF. Steroid contraceptive use and cervical dysplasia: increased risk of progression. Science. 1977 Jun 24;196(4297):1460-2. doi: 10.1126/science.867043. PMID: 867043.

- Misczynski M, Stern E. Detection of cervical and breast cancer: a community-based pilot study. Med Care. 1979 Mar;17(3):304-13. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197903000-00008. PMID: 763008.