Scientists have launched a global research network to combat deadly strep A infections that can trigger sepsis and heart damage in children.

The iSpy Network (the name comes from “immunity to Streptococcus pyogenes”) is led by Imperial College London and the University of California San Diego (UC San Diego), with funding from the Leducq Foundation. iSpy brings together 28 investigators from 11 countries, including experts in immunology, infectious disease, and epidemiology.

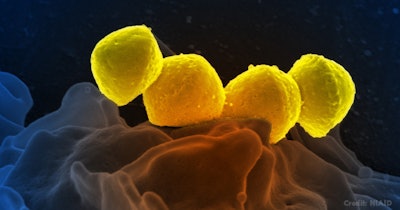

Each year, around half a million people around the world, including many children and young people, die because of serious Group A streptococcal (strep A) bacterial infections.

The iSpy Network will deploy a range of “state-of-the art techniques” to probe strep A immunity which should do much to alleviate the burden of strep A across the world, said professor Victor Nizet of UC San Diego, who leads one of two iSpy sub-networks, called iSpy-EXPLORE.

Strep A is highly transmissible and spreads from person to person. While most cases are relatively mild – affecting only the skin or throat – some infections can lead to deadly sepsis or autoimmune damage to the heart. There is currently no vaccine available for Strep A.

Unlike children, most adults are immune to strep A sore throats and skin infections. However, both groups are very susceptible to the invasive form of the infection. Repeated exposure to strep A infection can also cause autoimmune damage to the valves of the heart, known as rheumatic heart disease (RHD), which affects an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

The overwhelming burden of disease is shouldered by low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs), where there is more invasive disease and a lack of interventions for RHD patients who may require cardiac surgery. Partners in the iSpy Network – including in The Gambia, South Africa, Brazil, and Fiji – will collaborate to gain a better understanding of the body’s immune response to strep A and determine the most effective way to vaccinate against it.

“At present we don’t fully understand how immunity to strep A develops over time and if there are specific antigens (parts of the bacterium) that are more important for targeting by the immune system or future vaccines,” said Shiranee Sriskandan, a professor at Imperial College’s Department of Infectious Disease, who heads a second subnetwork (iSpy-LIFE).

“It’s also unclear how overreaction by the immune system to strep A – what we might call ‘bad’ immunity – leads to RHD and how that differs from the ‘good’, protective immunity we’d like to see,” she said.

The iSpy-LIFE sub-network will carry out studies in young children, school-age children, and adults to investigate how “good” immunity to strep A develops in children after they naturally acquire infections over time. The iSpy-EXPLORE subnetwork will investigate the nature of protective immune cell and antibody responses in experimental animals that receive the most promising strep A vaccine candidates currently in development. It will also examine how the human immune system reacts when healthy volunteers are experimentally challenged with Strep A infections.

John McCormick, a professor in the department of microbiology and immunology at Western University in London, Ontario, and scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute, will be part of the iSpy Network. His research focus is the study of bacterial toxins from Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.

“A major goal of this grant is to understand the key parts of the bacteria that could be used for developing an effective vaccine to protect against these types of infections,” he said.