Scientists have hailed study results showing the high accuracy of a blood test that “could revolutionize” diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

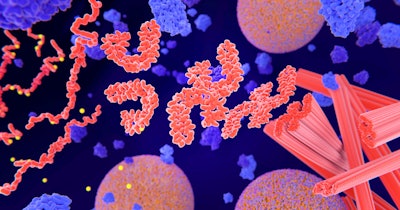

The test for p-tau217, a form of the protein tau which is a hallmark protein of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), was just as accurate as advanced testing like spinal taps and brain scans in showing AD pathology in the brain.

Based on their findings published in JAMA Neurology, the researchers say that such a blood test may eventually enable screening for people over 50 with only those at high risk of disease needing further investigation.

While the use of blood biomarkers as an AD diagnostic tool has shown promise, wider evaluation has been hindered by limited availability of commercial assays.

Researchers from Gothenburg University in Sweden examined a commercial test called the ALZpath pTau217 assay, which was developed by the company ALZpath and is currently available for research use.

It measures levels of p-tau217, a biomarker for changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Currently, identifying tau and amyloid beta buildups in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s relies on more invasive “gold standard” tests—positron emission tomography (PET) scans or lumbar punctures (spinal taps) which extract cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—which are costly and often hard to access.

The Gothenburg team, led by Nicholas J. Ashton, PhD, of the Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, analyzed data on 786 people from three observational cohorts in Canada, the U.S., and Spain. The participants, whose average age was 66, had amyloid and tau proteins confirmed with PET scans or CSF biomarkers; however, while some showed signs of cognitive decline, others did not.

The ALZpath blood test was found to be around 95% accurate at detecting P-tau 217 across all cohorts and just as good as the more invasive tests.

“Our findings demonstrate high accuracy in identifying abnormal Aβ and tau pathologies, comparable with CSF measures and superior to brain atrophy assessments,” Ashton and colleagues wrote.

The findings have raised hopes that an effective blood test could be used to screen for Alzheimer’s disease among people experiencing early memory loss and even before symptoms begin to show.

“A robust and accurate blood-based biomarker would enable a more comprehensive assessment of cognitive impairment in settings where advanced testing is limited. Therefore, use of a blood biomarker is intended to enhance an early and precise AD diagnosis, leading to improved patient management and, ultimately, timely access to disease-modifying therapies,” the researchers wrote.

“These results emphasize the important role of plasma p-tau217 as an initial screening tool in the management of cognitive impairment by underlining those who may benefit from antiamyloid immunotherapies,” they added.

The researchers estimate that some 80% of individuals could be diagnosed with a blood test alone without the need for other confirmatory tests.

“What’s particularly promising about the new study is that the researchers used a cut-off threshold to group people into those who were very likely to have Alzheimer’s, those who were very unlikely to have the disease, and an ‘intermediate’ group who would need further tests using conventional methods like lumbar punctures or PET scans,” said Dr. Sheona Scales, director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK.

“Using a blood test in this way, the researchers predict, could reduce the demand for these follow-up tests by around 80%,” Scales said.

Both the authors and the wider research community acknowledge the need for further investigations to take place in real-world clinical settings and with a more diverse patient group. An effective blood test could help identify who is likely to benefit from emerging treatments to slow down Alzheimer’s disease and differentiate Alzheimer’s from other neurodegenerative disorders to guide other treatments, experts said.

According to media reports, the makers of ALZpath are in discussions with labs in the U.K. to launch it for clinical use this year.

Ashton and colleagues say that future studies “should prospectively evaluate plasma p-tau217 reference points in memory clinic populations with wider diversity to ensure optimized implementation, accounting for higher rates of important comorbidities.”