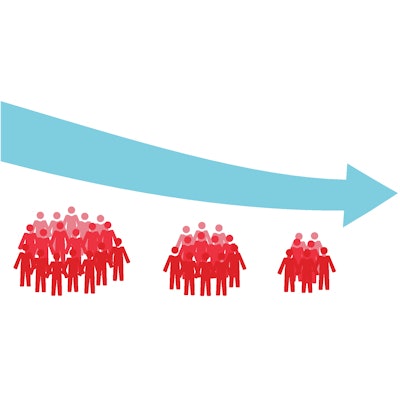

The number of active pathologists in the U.S. plummeted between 2007 and 2017 by about 17.5% and puts the country at risk of a shortage in the future, though a smaller workforce is currently handling a bigger load of cases, according to a study published on May 31 in JAMA Network Open.

The number of active pathologists dropped from 15,568 to 12,839 between 2007 and 2017, and in relative terms, that translates to a decline from 5.16 professionals per 100,000 in the population to 3.94 per 100,000 in 2017. In comparison, the number of pathologists in Canada increased by 20.45% (rising from 1,467 to 1,767), and the number of pathologists per 100,000 in the population increased from 4.46 to 4.81.

"Adjusted for population, the U.S. pathologist workforce is now smaller relative to other countries that have experienced major adverse events in clinical laboratory quality and delays in diagnosis," wrote Dr. Jason Park, PhD, the clinical director of the advanced diagnostics laboratory at Children's Health, Children's Medical Center in Dallas, and colleagues.

Trends for pathologists stand in contrast with other medical specialties. Between 2007 and 2017 in the U.S., the number of anesthesiologists grew by 7.85%, and the radiology workforce grew by 26.32%, they reported. For all specialties, the workforce grew by 16.61%.

"The decrease in number of U.S. pathologists is not only anomalous when compared with Canada, but also contrasts with increases in other hospital-based specialties (anesthesiology and radiology, for example) as well as the overall number of physicians," Park and colleagues wrote.

While the number of pathologists has declined, workload demands have been on the rise. The number of new cancer cases managed by pathologists rose by 41.73% in the U.S. between 2007 and 2017 versus 7.06% in Canada, the researchers noted. In contrast with physician specialties where the workload is limited by the number of patients who can be seen and treated, pathologists working in laboratories must manage all clinical specimens and materials from clinical colleagues within a specified period of time.

"Thus, a pathologist's workload is not capped by a specific number of patients, but rather expands to encompass all case materials generated by their clinical colleagues," the study authors wrote. "The dangers of overwork, diminishing quality, and diagnostic error are all reported in pathology."

When opportunity doesn't come knocking

The new workforce analysis was conducted in response to studies released in 2018 showing that the pathology job market was stable, yet pathologists appeared to be working harder than ever and trainees were having a hard time finding jobs. Park explained to LabPulse.com that a conversation with co-author Dr. David Metter about the apparent lack of interest on the part of recruiters relative to offers to residents in other specialties like radiology and anesthesiology spurred the study.

The dangers of workforce shortages in pathology in terms of risk for errors in diagnosis and delays in accessing services have been well-reported and studied in other countries, such as the U.K. and Canada. To date, in the U.S., attention has been on shortages in forensic pathology but not on the potential for diagnostic errors arising from the lack of pathologists. Park believes that while there has been a steep decline of pathologists in the U.S., the country is not at the point of having a shortage of professionals in the field.

The researchers analyzed the trends in the numbers of pathologists, radiologists, and anesthesiologists using data from the American Association of Medical Colleges Center for Workforce Studies Physician Specialty Data Book, which is based on the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile, and the Canadian Medical Association Masterfile. Furthermore, they assessed workload demands based on the number of cancer diagnoses.

Another key finding was the "stark distribution" of pathologists in U.S. states, Park noted to LabPulse.com. Some localities had a very high number of pathologists per population compared with very low numbers in other states, yet there haven't been reports of pathology groups having widespread shortages, he said.

Looking at data available for the years 2012 to 2016, the median number of pathologists per 100,000 population in 2016 was 3.68 -- the District of Columbia had the highest number at 15.71 per 100,000, and Idaho had the lowest at 1.37 per 100,000. Most states had negative growth in the number of pathologists between 2012 and 2016 -- only nine states had either zero growth or positive growth, the researchers reported.

"Interestingly, during this same period, every state had positive physician growth, ranging from +3.02% to +12.86%," Park and colleagues wrote.

Imperfect workforce data sources

Researchers acknowledged that limitations of the study include deficiencies in the AMA Masterfile; for example, these datasets reflect responses to surveys, which have low response rates.

"Regardless of its potential deficiencies, the AMA Masterfile is extensively used by government agencies, insurers, and physician credentialing services," they wrote. "A key strength of the AMA Masterfile is that it has been regularly updated and provides information relative to other medical specialties in the United States."

Park and colleagues noted that they can't reconcile the fact that the U.S. pathologist workforce is shrinking, but there is no increase in open positions or salaries. Anecdotally, it appears that university departments are still being selective in their hiring. Subspecialization has been a trend in recent years and, increasingly, fellowships are required, Park said.

"Unless you do at least one or two fellowships, you are really not considered competitive -- not even considered for a job," he said. "There are enough pathologists in the field that people can be choosy."

Furthermore, efficiency has improved with advances in information technology and management practices, the study authors wrote in JAMA Open Network.

"A single pathologist can now direct more laboratories and can interpret more cases than was previously possible. With these advancements, a smaller workforce is taking on an increasing workload," they wrote. "We hypothesize that the 17.53% decrease in active pathologists has been absorbed by increased efficiency, or at least increased elasticity in pathologist work tolerance."

New technologies such as artificial intelligence may further decrease the need for pathologists. Park suggested to LabPulse.com that workforce trends in pathology need to be monitored and publicized on a yearly basis.

"Maybe this is the new normal ... but at some point there is going to be too few people and we need to prepare for that," Park told LabPulse.com.

"Because of the potential consequences of a pathologist shortage, a comprehensive understanding of the current and future pathologist workforce is imperative," the authors wrote. "In contrast to other medical specialties, in which the public can directly observe inadequate staffing via delays in physician scheduling, the pathologist workforce is unique in that workload imbalance is not directly observed by patients and the public until a critical event occurs such as a diagnostic error or long delays in diagnosis."

A 'profoundly disquieting' report

The workforce report "is not a blip and it is serious," wrote Dr. George Lundberg, president and chair of the Lundberg Institute, in an accompanying editorial. Lundberg went on to describe the study as "profoundly disquieting" for an experienced pathologist such as himself who "really believes in the field." In Lundberg's view, the entry of for-profit corporations into the clinical laboratory field in the late 1960s and 1970s had a major impact on the pathology workforce.

"They used modern industrial management techniques and aggressive sales strategies to wrest away huge numbers and varieties of clinical lab tests from pathologist-directed hospital laboratories, pathologist-owned private laboratories, and physician office labs," Lundberg noted.

Another factor that has had an impact on the workforce is the decline in hospital autopsies starting in the 1960s, Lundberg said. Positive trends that could help reverse the decline in pathologists include efforts by the National Academy of Medicine to invigorate the autopsy as a tool for improved diagnosis and patient safety, with pathologists at the lead, and precision medicine. Precision medicine relies heavily on diagnostic genetics and is booming, so this is an obvious place for the growth of pathology work, Lundberg wrote.

How to boost interest in pathology

Dr. Adam Booth, the chief pathology resident at the University of Texas Medical Branch and chair of the College of American Pathologists (CAP) Residents Forum Executive Committee told LabPulse.com that the workforce report was "troubling" and noted that experienced pathologists are being lost at the same time as a large decline in the number of medical students going into pathology. The number of seniors applying for pathology positions dropped by 27.5% between 2008 and 2017, according to a study by Dr. Ryan Jajosky et al published in Human Pathology (March 2018, Vol. 73, pp. 26-32).

The residents committee believes that there is a lack of awareness of exposure to pathology during medical school and a lack of awareness of the many opportunities in the field, including subspecialties that involve more interaction with patients. CAP will be launching a new campaign on its website in August to raise awareness about pathology careers, which will include video interviews with current residents and details about the job market, Booth said.