The best way to assess awareness and adoption of laboratory practice guidelines by personnel is through print and electronic surveys, according to a study funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and published online June 18 in the Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine.

Laboratory practice guidelines provide a framework for the implementation of good laboratory practices. But the effectiveness of guidelines is determined in part by how extensively they are followed and implemented by lab personnel. So, it is important to identify gaps in knowledge and assess adoption to optimize laboratory testing practices in support of patient care.

Putting guidelines to the test

The College of American Pathologists (CAP) has developed 17 practice guidelines and has updated some of them over the years. But have they been effective?

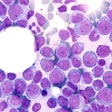

In 2013, CAP received a five-year cooperative agreement grant from the CDC to increase the effectiveness of its guidelines. First, CAP set out to determine the awareness and adoption of two guidelines covering immunohistochemical (IHC) assay validation and the initial workup of acute leukemia.

Lead author Dr. Jeffrey Goldsmith, director of gastrointestinal pathology at Boston Children's Hospital, and colleagues undertook baseline surveys for IHC and leukemia in 2010 and 2015, respectively. Then, to measure how well the guideline recommendations were adopted, they performed a follow-up study consisting of surveys, telephone interviews, and focus group discussions for laboratories that perform IHC testing. Eventually, the researchers also plan to do a follow-up study on acute leukemia.

Written surveys get better response

To validate the IHC guideline, the researchers analyzed 1,624 paper and electronic survey responses, 40 telephone interviews, and discussions with five focus group participants. They found that the response rates for these three validation modalities were 46%, 13%, and 3%, respectively. Most respondents were aware of the guideline and had adopted most or all of its recommendations, Goldsmith and colleagues reported.

Based on the higher response rate, the written practice surveys, both paper and electronic, were most effective in evaluating the awareness, adoption, and effectiveness of laboratory practice guidelines. Telephone interviews and the focus group provided opportunities to examine peripheral issues of guideline implementation not addressed in the written surveys, but they were labor-intensive, expensive to undertake, and generally inefficient for acquiring useful feedback. This is often due to a lack of participation by laboratorians, the researchers noted.

"In our experience, written surveys, which were available in both paper and electronic format, showed the best ease of use for both developers and participants, a good response rate, and quantitative results that were readily analyzed and interpreted," they wrote.

"By using the same questions in both the baseline and follow-up surveys, we were able to measure differences and draw more accurate comparisons about the differences found after IHC validation [laboratory practice guideline] publication," Goldsmith and colleagues added.

The telephone interviews were conducted by a contracted consultant at a cost of $30,000. The CAP database used to identify participants contained several contacts within an organization, making it a challenge to find the right individual who also was willing and had the time to discuss the nuances of implementing new guideline recommendations in the IHC laboratory.

Furthermore, many potential interviewees didn't want to be interviewed because they felt the time investment was too much of a burden for what they considered simple market research.

"At times, there was a perception of intrusion by the independent interviewer and resistance in answering the questions; however, the feedback that was obtained was valuable," Goldsmith and colleagues wrote.

The focus group session was the most complicated approach for the investigators. To reach the intended audience of pathologists and nonpathologists, the researchers wanted to run a focus session at a national meeting attended by both groups, but this proved to be difficult to arrange logistically. The researchers did not have access to the attendee list, so hundreds of invitations were sent out with only a limited return. Still, they held the focus group, and the ensuing dialogue and interaction led to suggestions for improvements in communication.

In contrast, the larger number of written survey participants made it possible to reach a more diverse population and create a more accurate, data-driven picture of existing gaps in the awareness, adoption, and effectiveness of laboratory practice guidelines, the researchers concluded.