Nearly half (47%) of the world's population has little to no access to diagnostic testing, including the ability to do cultures to identify microorganisms or access to a chemical analyzer or to a hematology analyzer, according to a report released on October 6 in the Lancet journal.

The objective of the report was to quantify the state of diagnostics across the globe, according to Susan Horton, one of the members of the Lancet Commission on diagnostics who contributed to the preparation of the report and a professor of global health economics at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

The commission members used definitions from the World Bank Atlas to categorize low-income, lower middle-income, upper middle-income, and high-income countries using U.S. currency. Low-income economies were defined as those with a gross national income (GNI) per capita of $1,054 or less in 2020, and lower middle-income was defined as economies with a GNI per capita of between $1,046 and $4,095. Upper middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $4,096 and $12,695, and high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,696 or more. The authors grouped lower middle-income economies and upper middle-income economies together and used the term middle-income economies.

The report authors estimated that 1.1 million premature deaths that occur annually in low-income and middle-income countries could be prevented by decreasing the diagnostic gap for six priority conditions including diabetes, hypertension, HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis B infection, and syphilis amongst pregnant women. The report authors also noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the crucial role of diagnostics in healthcare, and that without access to diagnostics, delivery of universal health coverage, antimicrobial resistance mitigation, and pandemic preparedness cannot be achieved.

The authors of the report noted that patients in low-income and middle-income countries generally have to travel to referral hospitals for diagnostic tests such as a complete blood count, blood chemistry, basic bacteriology, and any form of imaging. These referral hospitals often may only be in one urban center of a country.

Generally, primary health centers in low and lower-middle income countries tend to be very short of laboratory tests, according to Horton.

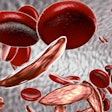

"You can't test for things like hepatitis B, and hepatitis B is quite common in countries like Nigeria," Horton said. "It is not good if you can't test for that. Tests for sickle cell anemia are not available, and that is quite common in West Africa. In addition, it is very difficult to perform microbiology culture for bacteria, fungus and parasites."

Prescribers will tend to overprescribe to individuals based on empiric or presumptive diagnoses in the absence of laboratory information, Horton said.

"If you don't have that [laboratory values], then physicians overprescribe things like antimalarials and antibiotics," Horton said, noting the practice of overprescribing contributes to growing antibiotic resistance.

Testing for blood sugar during pregnancy is not widely available at the primary care level, Horton pointed out.

"You need to figure out who needs to go to the hospital to be tested for gestational diabetes," she said. "Testing for gestational diabetes cannot be done at the primary level."

The World Health Organization in 2016 made recommendations for antenatal care, namely that all pregnant women should receive six pathology and laboratory medicine tests (i.e., testing for urine protein, hemoglobin, HIV, glucose, syphilis and, where prevalence warrants, tuberculosis). This report found that women can obtain these tests about half of the time in low-income countries.

The members of the commission noted that availability of diagnostics is somewhat correlated with country income, particularly at the level of primary care. Both Namibia and Senegal, the two countries with the highest per capita income, had the greatest availability of diagnostics. The countries with the lowest availability of diagnostics were also those with the lowest income: Malawi, Uganda, Rwanda, and Nepal.

The report authors released 10 recommendations to remedy the lack of access to diagnostics which include making point-of-care tests for key conditions available at all primary health centers and measuring the proportion of the population with access to an appropriate set of basic diagnostic tests at all primary health centers, including rapid tests for about 10 key health conditions and ultrasound.

The authors stated that the diagnostic gap that has been identified has adverse consequences for the burden of disease. The authors of the report noted that there can exist infrastructure barriers, particularly in rural settings, to support diagnostic services for laboratory medicine such as limited access to stable electrical supplies, clean water, reliable internet connections, and systems for transporting specimens.

The authors noted that in tropical or semitropical climates, without control of ambient climate, the storage of reagents and supplies can be problematic, and performance of laboratory equipment may be suboptimal.