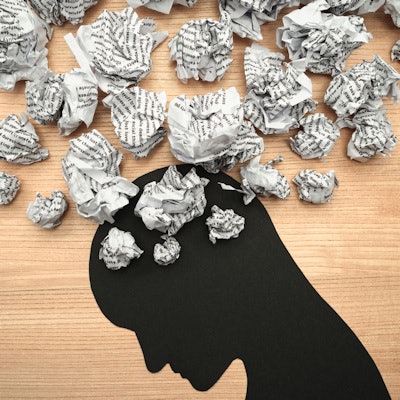

Pharmacogenomic testing that sheds light on drug-gene interactions can influence the selection of antidepressant medication and help caregivers avoid prescribing antidepressant medications that could lead to negative clinical outcomes, according to research published July 12 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

In the study, the patients being treated for major depressive disorder (MDD) who received pharmacogenomics testing also experienced better depression outcomes soon after they were tested.

The genes tested by scientists at the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia and colleagues elsewhere do not specifically relate to depression but to how a patient metabolizes medications once they have been administered.

"Some of these genes will cause the medications to metabolize much faster than normal. Others will cause the drugs to metabolize much slower than normal, which means you'll end up with a lot of medication in your body," Dr. David W. Oslin, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

A drug-gene interaction is an association between a medication and a genetic variant that may affect a patient's response to a drug therapy. With that information in hand, a provider would be better able to select the appropriate dosage for a specific patient. The researchers found that pharmacogenomic testing targeting drug-gene interactions in MDD helped providers select a drug treatment that was more appropriate for a particular patient because he or she better metabolized the drug.

The finding has implications for the prescribing of antidepressants because selecting effective medications for treating MDD is an imprecise practice, with remission rates of about 30% for the initial treatment.

The study investigators used the GeneSight Psychotropic test from Myriad Genetics, a pharmacogenomic test for 64 medications commonly prescribed for depression, anxiety, ADHD, and other psychiatric conditions.

"The results demonstrate how veterans may be helped by clinicians who provide personalized medication treatment and how such treatment can help make a positive impact on their lives, their families’ lives, and their communities," Paul Diaz, president and CEO, Myriad Genetics, said in a statement.

Patients who were enrolled in the pragmatic, randomized clinical trial were initiating or switching treatment with an antidepressant drug. The study included approximately 1,944 patients from 22 Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers who were randomized evenly, with half receiving pharmacogenomic testing and the other half receiving usual care.

Results from a commercial pharmacogenomic test were given to clinicians in the 966-member pharmacogenomic-guided group. The 978-member comparison group received usual care and access to pharmacogenomic results after 24 weeks.

The scientists found a marked shift in prescribing away from medications with significant drug-gene interactions or moderate drug-gene interactions. Overall, approximately 59% of the patients in the pharmacogenomic testing group received a medication with no predicted drug-gene interaction, compared with about 26% in the control group.

More specifically, the estimated risks for receiving an antidepressant with no, moderate, or substantial drug-gene interactions for the pharmacogenomic-guided group were 59.3%, 30%, and 10.7%, respectively, compared with 25.7%, 54.6%, and 19.7%, respectively, in the usual care group. The researchers defined that difference as "statistically significant and clinically meaningful."

Among patients with MDD, pharmacogenomic testing for drug-gene interactions reduced the prescription of medications with predicted drug-gene interactions compared with usual care. "The pharmacogenomic-guided group was more likely to receive a medication with a lower potential drug-gene interaction," the investigators wrote.

Remission rates over 24 weeks were greater among patients whose care was guided by pharmacogenomic testing than among those in usual care, but were not significantly greater at the 24th week, when 130 patients in the pharmacogenomic-guided group and 126 patients in the usual care group were in remission. Essentially, providing test results had a small nonpersistent effect on remission rates, the scientists reported.

In supplemental material, the researchers noted that the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in patients had a profound negative impact on remission from depression. The patients with PTSD responded poorly to antidepressants.