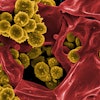

Genes that make bacteria resistant to antibiotics are more widespread in our environment than was previously realized.

A study from Sweden, published recently in Microbiome, shows that bacteria in almost all environments carry resistance genes, potentially spreading and magnifying the problem of untreatable bacterial infections.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), antibiotic resistance is one of the top 10 threats to global health, threatening to send medicine back to a time when infections including pneumonia, tuberculosis, and infected wounds could not be easily treated. According to the UN Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance, 700,000 people die each year from antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. While the genes that make bacteria resistant have previously been studied, the focus has been on identifying resistance genes already prevalent in pathogenic bacteria.

The researchers instead sought to analyze new forms of resistance genes in order to learn how abundant and how widespread they are. They traced the genes in thousands of different bacterial samples from different environments, including in and on people, in the soil, and from sewage treatment plants.

“Prior to this study, there was no knowledge whatsoever about the incidence of these new resistance genes,” co-author Erik Kristiansson, professor of mathematical sciences at Chalmers University of Technology, said in a statement on Tuesday. “Antibiotic resistance is a complex problem … we need to enhance our understanding of the development of resistance in bacteria and of the resistance genes that could constitute a threat in the future.”

Using metagenomics, a methodology that allows the analysis of vast quantities of data, the researchers analyzed a total of 630 billion DNA sequences. They identified new resistance genes in places where they had previously been undetected, potentially constituting an overlooked threat to human health.

The study showed that new antibiotic resistance genes were present in bacteria in almost all environments, including human microbiomes. The resistance genes in bacteria that live on and in humans and in the environment were ten times more abundant than those that were previously known. Furthermore, of the resistance genes found in human microbiome bacteria, 75% had not previously been known at all.

The researchers are currently integrating the new data into an international project — Establishing a Monitoring Baseline for Antibiotic Resistance in Key Environments (EMBARK) — which aims to take samples from sources including wastewater, soil, and animals in order to better understand how antibiotic resistance spreads between humans and the environment.

“It is essential for new forms of resistance genes to be taken into account in risk assessments relating to antibiotic resistance,” co-author Johan Bengtsson-Palme, assistant professor of life sciences at Chalmers University of Technology, added in the statement. “The techniques we have developed enables us to monitor these new resistance genes in the environment, in the hope that we can detect them in pathogenic bacteria before they are able to cause outbreaks in a healthcare setting.”