A new study shows that a blood test can detect toxic oligomers implicated in the development of Alzheimer’s years before symptoms of cognitive decline manifest.

Furthermore, the blood test, known by the acronym SOBA from “soluble oligomer binding assay,” may have applications for other diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia, with simple modifications.

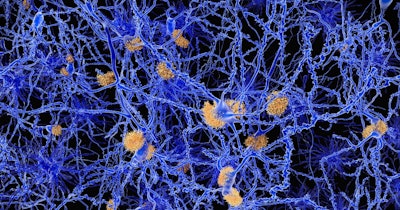

The study, published the week of December 5 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reports that the SOBA test detects levels of oligomers formed from aggregations of misfolded amyloid beta proteins that clump together. Through a process yet to be understood, these oligomers result in the development of Alzheimer’s.

Led by researchers from the University of Washington (UW), the study team tested SOBA on blood samples from 310 participants who had made the samples and relevant medical records available for Alzheimer’s research. When the blood samples were taken, the subjects were recorded as having no signs of cognitive impairment, mild cognitive impairment, or Alzheimer’s or another type of dementia.

SOBA detected oligomers in 52 of the 53 samples from participants with cognitive impairment or dementia who had subsequently died from Alzheimer’s disease, as documented by autopsy.

Moreover, while SOBA did not detect oligomers in most members of the control group, it did detect them in 11 control-group members with no signs of cognitive impairment. Follow-up records for 10 of those 11 participants were available; in the years following the samples being taken, all 10 had developed cognitive impairment ranging from mild to pathology consistent with Alzheimer’s disease.

In other words, SOBA detected oligomers indicating cognitive decline long before symptoms of cognitive decline had developed in these 10 individuals. As SOBA did not detect oligomers in samples from individuals in the control group who did not develop cognitive decline subsequent to the blood samples being drawn, these results point to the critical role that oligomers have in the development of dementia, the researchers noted.

SOBA was designed to exploit a distinctive feature of the oligomers which has been previously investigated by the research team: the alpha sheet. Alpha sheets are the distinctive structures formed when misfolded amyloid beta proteins clump into oligomers; alpha sheets tend to bind to other alpha sheets.

SOBA incorporates a synthetic alpha sheet that can bind to oligomers in blood or cerebrospinal fluid samples. Standard methods are then used to confirm that the attached oligomers are made up of amyloid beta proteins.

Furthermore, the researchers have determined that other diseases -- such as Parkinson’s -- are associated with the formation of alpha sheets in the production of the toxic oligomers. They have suggested that SOBA could be readily modified for use in detecting these diseases as well.

The research team is working with scientists at AltPep, a UW spinout company, to develop SOBA into a diagnostic test.

“What clinicians and researchers have wanted is a reliable diagnostic test for Alzheimer’s disease -- and not just an assay that confirms a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, but one that can also detect signs of the disease before cognitive impairment happens,” said senior author Valerie Daggett, professor of bioengineering at UW, in a statement. “That’s important for individuals’ health and for all the research into how toxic oligomers of amyloid beta go on and cause the damage that they do. What we show here is that SOBA may be the basis of such a test. We believe that SOBA could aid in identifying individuals at risk or incubating the disease, as well as serve as a readout of therapeutic efficacy to aid in development of early treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.”