Scientists have created a blood test that they believe can detect Alzheimer's disease with higher accuracy than a brain scan, according to a study published in Neurology on August 1.

Researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a blood test that measures beta amyloid. The test is not yet ready for clinical use, but the study findings show that using a blood test to detect brain changes of early Alzheimer's disease is moving closer to becoming a reality.

Their research included participants from longitudinal studies of memory and aging at the university. The scientists analyzed blood samples and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from 158 people (age range, 46.1 to 86.9 years) with mostly normal cognitive functioning levels taken within 18 months of the patients undergoing amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Using an immunoprecipitation and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry assay, they measured plasma beta amyloid (Aβ) 42 and Aβ40 to see if it could accurately diagnose brain amyloidosis, with amyloid PET and CSF p-tau181/Aβ42 as reference standards.

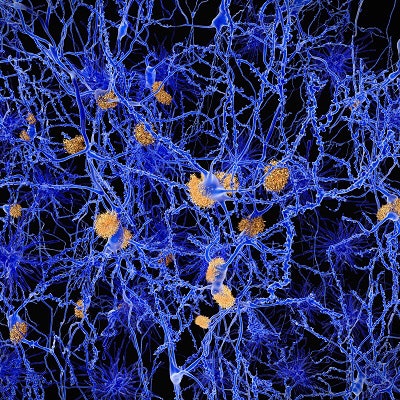

After looking at the blood test results and other factors that can impact a person's risk of Alzheimer's disease, including age and genetic risk factors such as the variant APOE4, the researchers determined that the blood assay was 94% accurate in diagnosing brain amyloidosis in patients.

The test was equally accurate in those who showed no signs or symptoms of the disease, according to the researchers. Mass spectrometry detected the buildup of amyloid in the brains of individuals who had no symptoms and negative PET scans. The scans only detected the accumulated amyloids years later, they found.

More rapid, less costly detection in the future

The test combined with age and genetic risk factors can accurately diagnose brain amyloidosis and also be used to screen individuals with normal brain function, the study authors concluded.

Furthermore, a blood-based biomarker would allow for faster, less expensive screening for individuals in prevention trials, in which negative amyloid PET scans rates are often about 70%, they noted.

"If further validated, this assay will accelerate progress toward an effective therapy for AD by decreasing the time, cost, and risk of drug trials, and one day enable a blood test in the clinic to identify patients who could benefit from disease-modifying treatment," wrote the study authors, led by Dr. Suzanne Schindler, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology at Washington University.