An artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm can identify patients who have a 25-fold higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer within three to 36 months, according to a poster presentation at this week’s annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) in New Orleans.

A team of researchers from the U.S. and Denmark used electronic health record (EHR) data from the Danish National Patient Registry to train their algorithm and then tested it on electronic medical records from Mass General Brigham Health Care System in Boston. Their model proved to be highly accurate for predicting patients at high risk for pancreatic cancer on large datasets from both countries.

"These results indicate the potential of advanced computational technologies, such as AI and deep learning, to make increasingly accurate predictions based on each person's health and disease history," said presenter Bo Yuan, a doctoral candidate at Harvard Medical School, in a statement from the AACR.

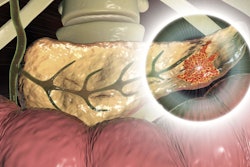

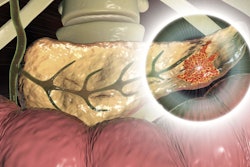

In their study, the researchers sought to develop an AI tool that can assist clinicians in identifying patients at high risk for pancreatic cancer, an aggressive cancer that is often undetected until later stages and has a relatively poor prognosis, according to co-first author Davide Placido, a doctoral candidate at the University of Copenhagen.

As there are currently no reliable biomarkers or screening tools that can detect pancreatic cancer early, the group sought to develop an AI tool that could help clinicians identify high-risk patients. These patients could then be enrolled in prevention or surveillance programs and hopefully benefit from early treatment, according to Yuan.

In contrast to other previously developed risk-prediction models, their algorithm was developed by incorporating concepts from language-processing algorithms, according to the authors.

"We were inspired by the similarity between disease trajectories and the sequence of words in natural language," Yuan said. "Previously used models did not make use of the sequence of disease diagnoses in an individual's medical records. If you consider each diagnosis a word, then previous models treated the diagnoses like a bag of words rather than a sequence of words that forms a complete sentence."

They trained the algorithm using EHRs from the Danish National Patient Registry, which included 6.1 million patients treated between 1977 and 2018. Of these, 24,000 developed pancreatic cancer. After inputting the sequence of medical diagnoses from each patient to teach the model the diagnosis patterns that were most significantly predictive of pancreatic cancer risk, they then tested the AI tool's ability to predict pancreatic cancer within three to 60 months after risk assessment.

When the algorithm was set at a threshold to minimize false-positive results, individuals deemed to be at high risk were 25 times more likely to develop pancreatic cancer from three to 36 months than patients below the risk threshold. The model yielded an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.87 on the training dataset from Denmark and, after being retrained on local data, an AUC of 0.88 on data from Mass General Brigham.

Although it's difficult to exactly pinpoint the diagnosis patterns that predicted risk, the researchers uncovered significant associations with certain clinical characteristics and the higher risk of pancreatic cancer development. These included diagnoses of diabetes, pancreatic and biliary tract diseases, and gastric ulcers.

The algorithm offers the advantage of integrating information about risk factors in the context of a patient's disease, according to Placido.

"The AI system relies on these features in context, not in isolation," Yuan said.

The researchers noted that their algorithm still needs to be evaluated in clinical trials.