A common laboratory test called a "comet assay" shows that radiation from technetium-99m (Tc-99m) single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) poses little risk of damaging a patient's DNA, according to a Brazilian group.

In a pilot study, researchers studied the effect of ionizing radiation on patients who underwent MPI exams, also known as nuclear stress tests. They used a comet assay, a standard lab test for detecting DNA damage in cells, to analyze patient blood samples before and after they underwent imaging, with results suggesting a small yet likely irrelevant amount of damage.

"There is an open field for the continuous evaluation of the effects of ionizing radiation on human DNA," wrote corresponding author Dr. Andrea Lorenzo, PhD, of the National Institute of Cardiology in Rio de Janeiro (BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, September 3, 2022, Vol. 22:1, p. 394).

The overall radiation burden to the U.S. population doubled from the early 1980s to the mid-2000s, and the performance of millions of medical imaging procedures continues to raise concerns over increasing radiation dose and the potential cancer risk posed to the population.

While there is no direct evidence of cancer risk from SPECT MPI, several large epidemiological studies have projected an increased risk for patients, according to the authors. In this study, they hypothesized that a "bench level" approach using a comet assay may help elucidate the issue.

The researchers enrolled 29 patients without cancer, acute or autoimmune diseases, or recent surgery or trauma who were slated to undergo SPECT MPI with Tc-99m sestamibi at their hospital in Rio de Janeiro. They collected peripheral blood samples from patients before radiotracer injection (880.6 ± 229.4 MBq), and a second sample immediately before the patient left the hospital after imaging (between 60 and 90 minutes after tracer injection).

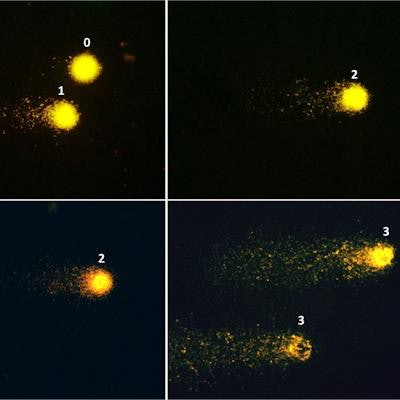

Fluorescence microscopy images (×400) showing examples of patterns of DNA damage in the comet assay. Left panel: Nucleoid structures depicting class 0 of damage (no tail) and class 1 (small tail). Middle panel: class 2 of damage (larger tail). Right panel: class 3 of damage (profound fragmentation, very large tail). Image courtesy of BMC Cardiovascular Disorders.

Fluorescence microscopy images (×400) showing examples of patterns of DNA damage in the comet assay. Left panel: Nucleoid structures depicting class 0 of damage (no tail) and class 1 (small tail). Middle panel: class 2 of damage (larger tail). Right panel: class 3 of damage (profound fragmentation, very large tail). Image courtesy of BMC Cardiovascular Disorders.The comet assay is based on single-cell gel electrophoresis technology and detects DNA bond breaks in blood T cells through visualization under a fluorescence microscope. DNA strand breaks determine the variable size of the "comet tail," which was visually scored by three experts into four categories: 0 for no damage (no tail), 1 for small damage; 2 for large damage, and 3 for full damage (very large tail).

Most cells (approximately 70%) remained without DNA fragmentation (class 0) after tracer injection and imaging, according to the findings. There were nonsignificant increases of classes 1 and 2 of damage. Class 3 was the least frequent both before and after radiotracer injection, yet displayed a significant, 44% increase after injection.

"Importantly, even though there was an increase of the damage index and of classes 1-3 of damage, most cells remained in class 0," the group wrote.

Ultimately, human cells have self-protective mechanisms that contribute to reduced radiation effects, the authors noted. In response to DNA damage, cells have been shown to activate repair genes. Thus, even though small amounts of DNA damage may occur due to SPECT MPI, the amount is likely biologically irrelevant, they wrote.

This study was also performed with relatively high radiotracer doses, and therefore the amount of DNA damage might have been overestimated and may currently be substantially less with hardware improvement and new test protocols, the group added.

Still, this was a pilot study, and additional research on the radiation risk from SPECT MPI is warranted, they wrote.

"New imaging protocols, using stress-only strategies, or new imaging hardware and software, which allow the use of very small radiotracer doses, may lead to further reductions in radiation-induced DNA damage from MPI," Lorenzo and colleagues concluded.