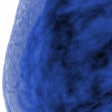

The U.S. Endocrine Society's updated practice guideline for preventing heart disease and type 2 diabetes, published online on July 31, clarifies current thinking on metabolic risk and includes a recommendation for more frequent testing of individuals with prediabetes.

People with prediabetes should be screened at least annually, according to the primary prevention guideline for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which was published by Dr. James Rosenzweig, an endocrinologist at the Hebrew Rehabilitation Hospital in Roslindale, MA, and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (September 2019, Vol. 104:9).

The guideline, which was co-sponsored by the American Diabetes Association and the European Society of Endocrinology, is an update of recommendations published over a decade ago by Rosenzweig et al (J Clin Endocrinol Metab, October 2008, Vol. 93, pp. 3671-3689). At that time, experts recommended testing individuals with prediabetes every one to two years.

The new guideline advises the following tests as options for measuring elevated blood sugar: fasting plasma glucose (FPG), oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). The old guideline recommended fasting plasma glucose tests.

"The FPG test is automated and inexpensive but reflects the glycemic state at only a single time point. The OGTT is more sensitive but also more time-consuming, costly, and variable than the FPG test," the guideline authors noted. "However, some evidence suggests that the OGTT is a better predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality than FPG."

"HbA1c is a more long-term measure of glycemia with less sensitivity but also less variability than glucose tests and can be performed in the nonfasting state," they added.

5 metabolic risk factors

Like the last version, the new guideline outlines five key metabolic risk factors: increased waist circumference (abdominal fat), elevated triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), high blood pressure, and high blood sugar. These are not exclusive but rather are complementary to other clinical measures, such as body mass index and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), for risk assessment.

One significant difference with the new guideline is a focus on screening individuals ages 40 to 75, as this time around the authors noted the evidence is strongest for this part of the population. For those in this age range who have least one risk factor, the guideline advises screening every three years for all five key risk measures and assessment of 10-year ASCVD risk when appropriate.

Other important changes in the new guideline include the following, according to Rosenzweig and colleagues:

- The focus is now more on reducing the risk for ASCVD and type 2 diabetes, rather than on defining metabolic syndrome itself.

- Hemoglobin A1c is now included as a way of measuring glycemia as a metabolic risk factor. There are now established international standardization programs for HbA1c laboratory assays, the authors noted. An HbA1c assay without analytic interference should be used.

- Targets for LDL are expressed in absolute values and relative terms, versus just absolute terms.

- A new method for calculating 10-year risk developed by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) is now recommended, whereas the Framingham risk scoring was used previously.

- Definitions of ASCVD risk in primary prevention have been updated. Moderate is defined as a 10-year ASCVD score between 5% and 7.5%, compared with less than 10% in the last version. High cardiovascular risk is defined as a 10-year risk score greater than 7.5%, compared with greater than 20% in the last edition.

Wanted: Validated lab tests

Furthermore, "testing for additional biological markers (e.g., high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) associated with metabolic risk should be limited to subpopulations," the guideline authors advised.

Many additional tests may be done to look at cardiovascular and diabetes risk, but the authors felt those were unnecessary and they kept the focus on simple tests, Rosenzweig commented in an interview with LabPulse.com. He also said that for diagnostic purposes, markers such as blood sugar and cholesterol should be tested in clinical labs. These tests are offered on point-of-care devices in doctors' offices, but they are not clinically accurate enough to diagnose diabetes or hypercholesteremia, though they are useful for following levels over time.

"We want validated lab tests -- those are done in clinical laboratories," Rosenzweig said.

Embracing LDL targets

Individuals with metabolic risk factors are assessed for 10-year risk of ASCVD and may be managed accordingly. The guideline stresses intensive behavioral modification, including exercise and a 5% loss of body weight, in line with the last version; drugs may also be used if goals are not achieved.

The guideline looks at LDL-C in line with the traditional focus on reaching certain goals through the use of statins when necessary.

"Decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis depending on estimates of likely benefits [versus] risks in individual patients," the guideline authors wrote. "Statin therapy should be calibrated to reach the recommended low-density lipoprotein targets."

When it comes to LDL-C, Rosenzweig views the Endocrine Society's guideline as mostly in sync with the ACC/AHA recommendations, though with more of a focus on particular numerical targets (see table).

In their 2013 guideline on the management of blood cholesterol, the ACC and AHA moved strongly away from treating to LDL-C targets and toward reducing risk by a relative amount using the new risk calculator. However, in an updated guideline for managing blood cholesterol released in November 2018, the ACC/AHA seemed to backtrack, advising some targets for those at very high risk but a relative reduction in LDL-C for lower-risk groups.

"There was a tremendous amount of disagreement among various people related to whether or not we should treat to target," Rosenzweig recalled, adding that the latest ACC/AHA stance is more "nuanced."

| Endocrine Society practice guideline: Cholesterol targets | ||

| Patient profile | LDL-C target or % reduction | Advice for statin treatment |

| Adults with LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL | ≥ 50% reduction of LDL-C | High intensity |

| Age 40-75, no diabetes, LDL-C 70-189 mg/dL, 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5% | < 100 mg/dL or ≥ 50% reduction of LDL-C | Moderate or high intensity |

| Age 40-75, no diabetes, LDL-C 70-189 mg/dL, 10-year ASCVD risk 5% to < 7.5% | < 130 mg/dL or 30%-50% reduction of LDL-C | Consider moderate intensity |

| Age > 75, no diabetes, LDL-C 70-189 mg/dL, 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5% | < 130 mg/dL or 30%-50% reduction of LDL-C | Consider low intensity, after discussion with patient |

Addressing genetic risk

The latest guideline also includes a discussion about the use of genetic risk scores for type 2 diabetes. Genetic information can predict ASCVD and T2DM, the authors noted.

"However, correct implementation of polygenic risk scores for ASCVD/T2DM prediction is rarely seen in clinical practice, likely because there is a lack of data showing that this knowledge will truly change clinical decisions, individual behaviors, and ASCVD/T2DM outcomes," they wrote.

A healthy lifestyle is helpful regardless of genotype, the authors noted.

"Genomics integration may become more promising in primary prevention of ASCVD and T2DM if genetic determinants are identified of the degree of response to lifestyle interventions (such as degree of weight loss or changes in glycemia/lipids) or to specific aspects of behavioral changes (better response to physical activity, specific response to dietary components) to tailor our future interventions," the group concluded.